The coronavirus crisis has exposed the extent to which fair access to good healthcare is tangled in a web of politics, economics and social issues. Here five of our experts explore how Covid-19 interacts with such systems and structures to highlight priority areas for action now, and to propose a ‘new normal’ for public health after the crisis.

We take an in-depth look at various health effects and responses to Covid-19, including universal health coverage (UHC), mental health and equitable access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH). We also learn lessons from elsewhere, including from other pandemics such as HIV, while showing that responses need to be comprehensive, holistic, context specific, and engage public and private sectors and communities.

Emma Samman: Covid-19 is our chance to install universal health coverage for future generations

The coronavirus crisis has highlighted the danger of excluding people who can’t afford healthcare and the corresponding need to ensure universal access. This prompted panellists at a recent ODI event to press for universal health coverage (UHC) and offer some useful reflections.

Politicians and the public now have a laser-like focus on health, and how it links to the economy and education (subscription required). Some countries have taken steps towards UHC to tackle the crisis: Ireland and Spain have essentially nationalised private healthcare, while many African countries have waived user fees for Covid-19 tests and treatment.

Other current circumstances may also be advantageous to building universal health systems. Our research shows that most countries (71% of the 49 examined) moved to UHC following a crisis. Fragile contexts provide countries an opportunity to reflect on what they want to become and prioritise the need for unity. This can create political appetite for UHC and silence dissenters.

Wealth itself is not a major driver – state capacity appears more important, as does economic growth. The hoped for post-crisis economic bounce back could provide the fiscal space needed to fund investments in health. Finally, although transitioning to UHC is an iterative process, once countries establish UHC they tend not to go back: universal systems are robust, even when confronted by new shocks.

The problems won’t end there. Policy-makers will still face challenges ensuring all excluded groups are fully covered, as well as trade-offs between tackling Covid-19 and addressing other health needs, like vaccinations and cancer screening. UHC is not a panacea for over-stretched health systems, but acting now will help us rise to the coronavirus challenge and improve the health and wellbeing of generations to come.

Tom Hart: Covid-19 needs a renewed focus on primary healthcare

Low- and middle-income countries simply don’t have the money to respond to Covid-19 (PDF) in the same way rich countries do. They also began this crisis with far lower levels of government health spending. Per capita in 2017, this was $477 in China and $3,030 in the European Union, but only $69 across sub-Saharan Africa, supplemented by $25 of external assistance.

Lower income countries therefore face a difficult choice between spending on health versus spending to support incomes, businesses and the wider economy. Health budgets will need a significant boost to step up surveillance, testing, tracing and information campaigns and to be able to respond to the increased demand the health system will face.

Most African countries and donors prioritise spending on primary care. With Covid-19, a key risk is that these resources will be diverted to hospitals and intensive care units. Diverting resources for Ebola in West Africa may have more than doubled the death-toll from measles, malaria, HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis. Focusing on primary healthcare is also widely recognised as the most cost-effective and equitable way to progress towards universal health coverage. This is a ‘no regret’ policy.

Covid-19 is a political opportunity to invest in health, but it might also intensify competition for public resources within and beyond the health sector. To capitalise on this moment, countries will need to institutionalise transparent resource allocation decisions and make sure that this is aligned with the public finance management systems that do the hard work of translating policy decisions into resources on the ground.

Fiona Samuels: three things we overlook in the Covid-19 mental health crisis

One positive effect of Covid-19 is that it has increased discussion about mental health – in the news, in academia, and in politics. Coverage of how Covid-19 is affecting the mental health of different groups – young, old, refugees, migrants, health workers – is also very welcome. Despite this frenzy of interest, three important issues are often overlooked:

We need more information and planning for mental health action in low-income countries. Although we hear about (and can learn from) creative health responses to Covid-19 in low-income countries, there has been little on mental health. This raises concerns that recent gains made in addressing mental ill-health in these contexts may be lost in the rush to deal with the medical emergency of Covid-19. We need to start these discussions now to plan effective, holistic responses and build back better.

We must address the social realities that intersect with Covid-19 mental-health issues. We need to look beyond medical approaches to explore the social determinants of mental ill-health, including income and gender inequality, as well as social norms. Women and girls in low income countries are often more exposed to discriminatory gender norms which effect their mental health, including early marriage and domestic violence. Covid-19 related stress and isolation can compound these problems. We must address the underlying drivers of mental ill-heath as medical responses alone are insufficient.

We need to understand the range of mental health issues created by Covid-19. Fear, stress and anxiety are associated with lockdowns, but they can also be caused by the easing of measures and by real fears of job losses. Survivors may suffer trauma when re-living their experiences and when reintegrating into communities that stigmatise Covid-19. People with pre-existing mental ill-health may be triggered by the crisis – in the worst case leading to suicide. For those on psychiatric wards (and their carers), Covid-19 adds another set of challenges. Policy-makers must understand these issues to plan a comprehensive multi-level and multi-stakeholder response.

Carmen Leon-Himmelstine: what HIV and Ebola teach us about stigma, gender and poverty in the face of Covid-19

Covid-19 is presented as a uniquely disruptive disease. Yet epidemics like HIV and Ebola in low and middle-income countries can teach us some important lessons on how to respond to this crisis.

During the AIDS epidemic, many HIV positive sex workers, gay and bisexual men, and drug users were stigmatised, creating barriers to treatment and prevention. It’s already been reported that some groups, including people who have recovered from Covid-19 and health workers, have faced threats and accusations online and in their communities. Governments must publicly speak out and take actions against stigma and discrimination as part of their Covid-19 response. Initiatives to combat HIV/AIDS stigma can be taken as examples, such as the implementation of awareness raising campaigns by countries including Ireland and Mexico.

As research on HIV prevention shows, shaming drives risky behaviour underground. The New York guidelines (PDF) offer tips on having sex while minimising the risk of spreading Covid-19. Sadly, the economic impact of Covid-19 may push poor women and girls into transactional sex, increasing their risks of contracting HIV/STIs. Harm reduction strategies need to be implemented and supported by governments, following New York’s example by offering shame-free advice.

During the Ebola crisis, women and girls were also the hardest hit as traditional caretakers of the sick. Women comprise around 70% of health and social workers globally and do most of the world’s unpaid care work, increasing their infection risk. During Covid-19, providing protective equipment for unpaid home carers, as well as hospitals, is essential.

The Ebola crisis diverted resources away from other diseases like HIV, malaria and tuberculosis. In a similar way, Covid-19 could set the clock back on AIDS-related deaths to 2008 in sub-Saharan Africa. Countries must innovate to maintain essential services, from dispensing medicines to cover multiple months for chronic conditions, to treatment pick-up points and community-based approaches.

Ebola and HIV show us that we must act now on social stigma, risky behaviours and gender roles, without neglecting other essential health services and economic inequality to protect the most vulnerable from the fallout of Covid-19.

Vidya Diwakar: equitable access to WASH can fight Covid-19 today and boost public health for the long-term

Donors are already prioritising water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) in response to Covid-19, because they understand its impact on public health. But despite handwashing messages being the staple of most Covid-19 responses, countless marginalised communities still don’t have access to basic WASH services.

Many people living in or near poverty today don’t have access to clean water or affordable soap, making them more susceptible to Covid-19 transmission. Subsequent poor health resulting from the virus, reinforcing other health and non-health shocks, could push people further into poverty.

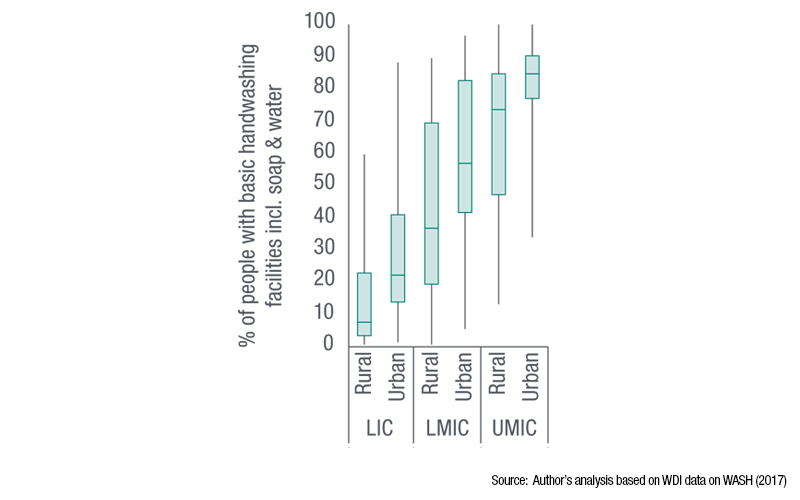

Slums and densely populated urban areas in low and middle-income countries often lack basic services and have irregular water supplies and poor sanitation. In rural areas, access to WASH is even more limited. The graphics below highlight this gap in terms of being able to wash your hands, although similar trends can be seen for drinking water and sanitation.

While more than two-thirds of countries have measures in WASH policies and plans targeting poor populations, less than 40% consistently finance or monitor these efforts. Vulnerable people need better access to WASH, for example by upgrading infrastructure in underserved areas and through subsidies, which should be monitored to ensure equitable distribution. Until then, NGOs and local groups may be needed to fill the gap.

The speed of delivery is crucial. The priority must be to provide basic handwashing for densely populated urban areas and poor rural communities. Some of this is already happening through social transfers, which should be expanded.

Stronger links between health and business authorities could improve WASH in high-density worker settings like markets. This would also invite different groups into WASH decision-making.

Reducing WASH inequality is a critical short-term response that can help limit the disproportionate impact of Covid-19 on people in or near poverty. In all of these attempts, empowering communities and working with people in poverty in the design and use of WASH services improves the sustainability of hygiene projects and their equitable roll-out, with long-lasting public health benefits.

Authors: Emma Samma, Tom Hart, Fiona Samuels, Carmen Leon-Himmelstine, VIdya Diwakar