By: Simone Schotte

An elderly woman works in the Abalama Bezehkaya garden in Guguletu, Cape Town, South Africa

Photo credit: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)

South Africa’s COVID-19 lockdown regulations are likely to have a devastating impact on the incomes of workers and their dependents, and already disadvantaged groups will suffer disproportionately from the adverse effects. Especially low-income earners performing jobs in precarious, informal sectors of the economy without unemployment insurance, limited access to healthcare and no back-up savings, are severely hit. The government’s decision to top-up the monthly social grants as a temporary relief measure during the corona virus pandemic was an important step in the right direction. However, the effective top-ups are significantly lower than previous estimates and may not be sufficient to provide significant relief to some of the most vulnerable people in the country.

The COVID-19 pandemic may have lasting effects on people’s means and opportunities to make a living

The COVID-19 pandemic poses important risks not only for people’s health but also economic well-being, which will extend well beyond the lock down. The severity of the effects will depend not only on how long the pandemic lasts and the government’s immediate relief measures, but also on the lasting consequences on people’s means and opportunities to make a living.

In this regard, I want to highlight two main channels with potential long-term impacts:

The expected slowdown in production and reduction in aggregate demand for goods and services may have long-lasting effects on the labour market. The World Bank projects that economic growth in 2020 will decline across Sub-Saharan Africa, hitting the region’s three largest economies hardest, including South Africa. Those who have lost their job or had to close their business during the lock down may have a hard time getting back on their feet. This also applies to those South Africans – particularly women – who had to suspend their labour market activities during the pandemic to take care of children or sick relatives.

The lock down of education institutions is going to cause major interruptions in students’ learning – both at the school and university level – potentially leading to higher dropouts of students from disadvantaged socioeconomic backgrounds. Students living in South African townships and villages generally do not have the basic infrastructure to continue remote learning, and may need to leave education to economically support their families.

Considering my previous research analysing poverty dynamics in South Africa, I find these two mechanisms particularly concerning.

Even in normal times, about 70% of those who experience downward mobility enter a situation of structural poverty that it is difficult to escape from

In a recent UNU-WIDER working paper, I use a mix of quantitative and qualitative research methods to illustrate the complex processes, livelihood strategies, and asset dynamics that condition movements into and out of structural poverty in South Africa, with special attention given to the urban population.[1] While conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, the main messages emerging from this research remain highly relevant in the current situation.

Across urban South Africa, the chances of moving up the income ladder are characterised by ‘sticky floors’ and ‘sticky ceilings.’ Except for the most and the least well-off, there is considerable mobility across income levels. However, for roughly half the people who start off from a situation of structural poverty and experience a rise in incomes, the escape from poverty is stochastic (or random), characterised by a limited accumulation of assets that could help facilitate successful long-run escapes from poverty. Conversely, close to 70% of those who start-off non-poor and experience downward mobility fall into a situation of structural poverty, where assets have been significantly depleted. Thus, among households with few buffers to protect their living standards, negative shocks to income can easily generate a poverty trap, which it is difficult to escape from.

Job transitions are among the main trigger events associated with poverty entries and exits

To better understand the building blocks that either pave or bar the way for structural poverty transitions, I conducted 30 life-history interviews between July and September 2017 in the township of Khayelitsha, situated about 30 kilometres south east of Cape Town’s city centre.[2]

Two main patterns were repeatedly observed:

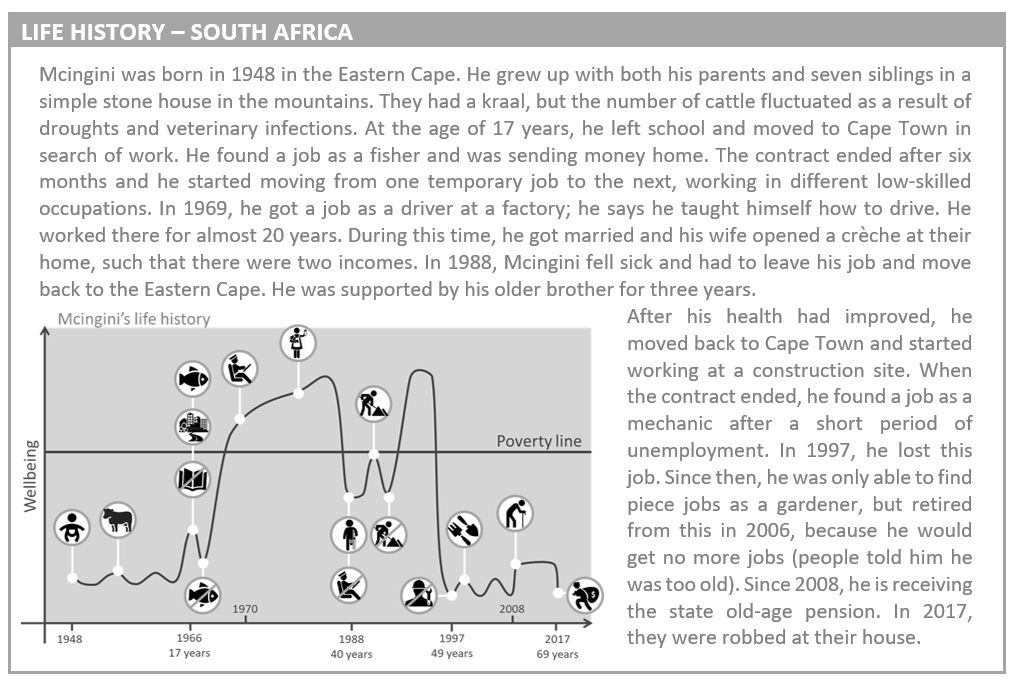

In contrast to those who remained structurally poor, those who experienced structural upward mobility were integrated into better-functioning family networks and were more successful in seizing opportunities to enhance their human capital, especially by gaining relevant work experience and certifications. They experienced an important gradual improvement in their standard of living, often facilitated by successful job-to-job transitions, with only short spells of unemployment in between. Importantly, at least some of these jobs were kept for prolonged periods of time (10-20 years). Mcingini’s [3] story summarised below illustrates this pattern. However, it also illustrates the vulnerability of those in jobs that are sufficiently well-paid to make a living while working, but which come without social security coverage, thus leaving them at high risks to slipping into poverty in times crisis, sickness or in later life.

In the cases in which persons experienced a structural decent into poverty, the impoverishment tended to occur in multiple linked steps, constituting a downward spiral. Respondents often experienced an accumulation of several negative and often interrelated events, which included job loss, sickness, the death of a close family member, being a victim of crime, experiencing the destruction of household property, domestic violence, and alcohol or drug abuse.

Summarising, transitions into or out of employment and job-to-job transitions were among the main trigger events associated with both poverty entries and exits. Functioning family networks, educational attainment and work experience presented key facilitating factors in this regard, while health shocks, crime, and domestic abuse were among the main risk factors.

This gives rise to concerns that the COVID-19 pandemic may not only present a temporary shock, but have lasting implications for poverty rates in South Africa through its effects on people’s health, education and employment prospects, as well potential knock-on effects on rates of crime and domestic abuse. The pandemic may not only have short-term income effects but also hamper people’s income generating activities in the longer term, as households will turn to liquidating their small savings and selling off productive assets to cope during the lock down period. In addition, reduced food consumption in times of hardship, school closures and the constraints that poor children face in online teaching can have a negative effect on human capital formation which can have long-term negative effects on earnings. For the millions of vulnerable South Africans whose livelihoods hang in the balance, an ambitious commitment by the state to confront these challenges will be decisive.

Footnotes:

[1] Analysing households’ access to, and holdings of, livelihood assets in terms of human, financial, physical, social, and geographic capital, the paper defines an asset poverty line that reflects the average endowment level associated with a living standard above poverty. On this basis, a household with a consumption level below the nationally defined cost-of-basic-needs poverty line, is classified as structurally poor if its asset position falls below the asset poverty line, and stochastically poor otherwise. Analogously, poverty entries or exits are defined as structural if accompanied by a depletion or accumulation of assets that moves the household across the asset poverty line, and stochastic otherwise.

[2] Khayelitsha closely resembles many of the context characteristics that typically condition the lives of the urban poor in South Africa. On the one hand, service delivery, economic activity, and opportunities for employment are generally better in urban than in rural areas and continue to entice rural-to-urban migration (roughly every second inhabitant was born outside of the Western Cape, almost all of whom migrated from rural areas in the Eastern Cape). On the other hand, rapid urbanization has left many on the fringes of society, resulting in a proliferation of informal settlements and increasingly densely populated townships, suffering from high unemployment and underemployment, socio-economic insecurity, and crime.

[3] Name has been changed for confidentiality.