How is COVID-19 impacting people living in, or at risk of, poverty in Zimbabwe? What policies are needed to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 on chronic poverty? CPAN’s COVID-19 Poverty Monitor is an ongoing research project that interviews people about their experiences of the pandemic. To find out more about the project, visit our blog about the global project. This bulletin dives into the main economic, health, food security and other concerns of those interviewed, as well as policies to minimise the impacts of COVID-19 suggested by the respondents.

Post-lockdown recovery

By early 2022 the lockdown in Zimbabwe eased as the threat of COVID-19 declined (Pindula news. 6 April 2022), with the situation returning to a ‘new normal’. This brought improved well-being for many. The impact of the lockdowns on people’s access to basic services lessened, declining from 21% in 2020 to 14% in 2021. Restrictions in agricultural markets have declined also, from 13% in 2020 to 10% in 2021 (2021 Rural Livelihood Assessment Report).

Income poverty remains high, and many people are extremely poor, although extreme poverty has fallen from a high of 49% in 2020 to 43% in 2021. Infant and maternal mortality rates have also fallen, educational attainment has improved, access to basic services has expanded and asset ownership has increased (ZIMSTAT and World Bank (2022). Zimbabwe Poverty Assessment: Core Poverty Diagnostics. Powerpoint presentation, March 7, 2022).

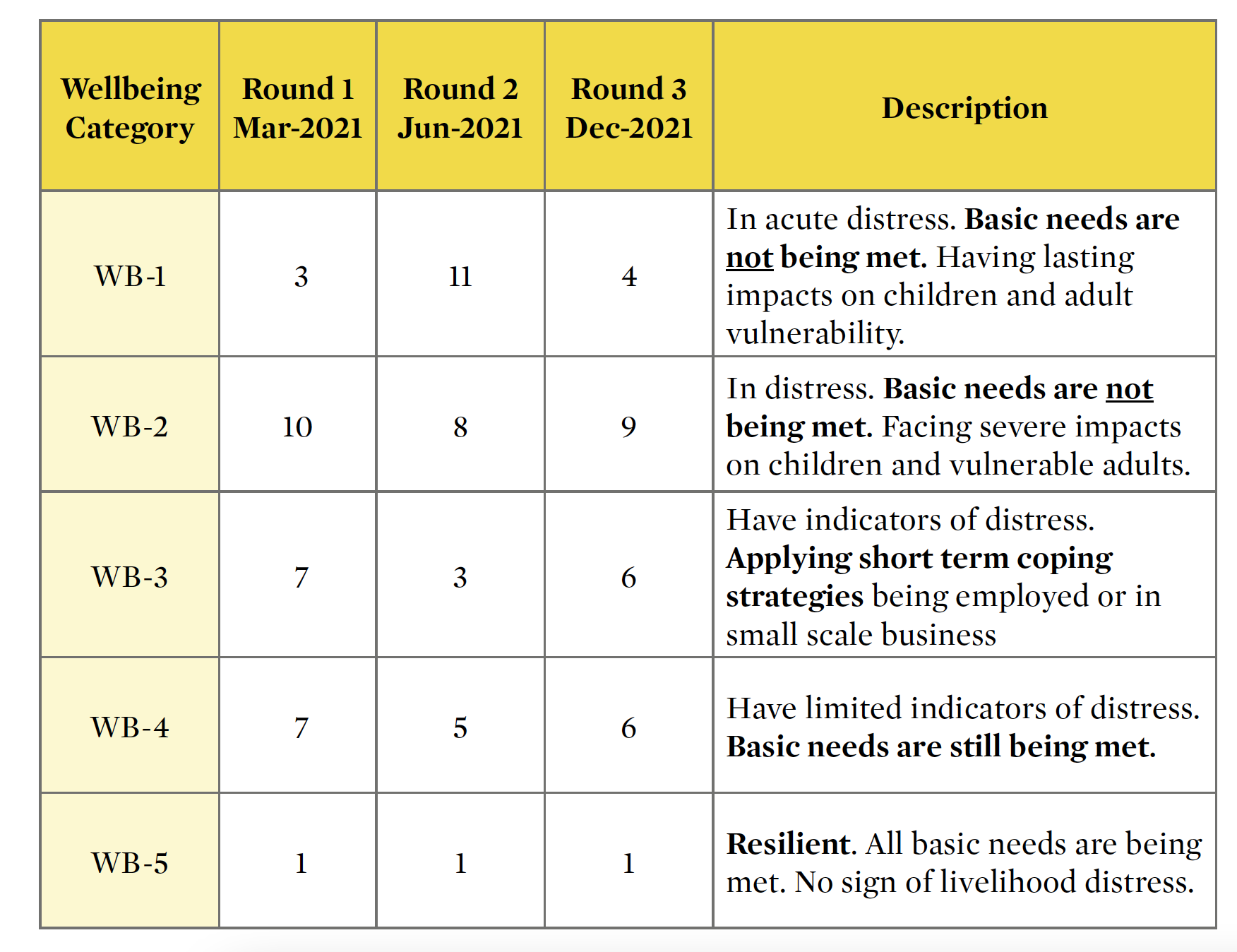

Thambo, 86, who is in the poor wellbeing group (see Table on wellbeing categories and characteristics), who lives with his orphaned grandchildren in Tsholotsho was relieved that access to healthcare services had improved:

“Since lockdown restrictions were loosened, it has become possible to travel to clinics and hospitals. Drugs are also now easier to access, even from omalayisha (informal transporters) since travel and courier services are slowly normalising.” Thambo, 86, poor well-being group, Tsholotsho

Thambo added that public gatherings for learning, social, economic, religious, and political purposes are now allowed. “Groups can now gather for all sorts of legal activities. This is good for developmental work, social and moral support of all our community members.”

Thenjiwe, a 55-year-old builder from Tsholotsho (poor wellbeing group), was enthusiastic about improved access to shops, markets, and services. “Yes, our little world has reopened so services have since become available near us.”

Bruce, a 50-year-old farmer and horticulturalist was relieved that things were getting better, back to pre-COVID-19 levels.

“Due to the relaxation of the lockdown, I am now able to access the Manhenga market to sell some farm produce and fresh vegetables. My income has since improved as compared to last year when all the markets were closed.” Bruce, 50, vulnerable but not poor well-being group, Bindura.

His life has transformed, and he is living better. He can now afford three meals per day with bread and eggs at breakfast, and sadza (maize meal porridge) and meat two to three times a week.

“Those challenges are things of the past and I can now afford some little things that I could not buy during the time that we last spoke (the first-round interview in November 2021). The price of farm inputs is very high.” Bruce, 50, vulnerable but not poor well-being group, Bindura.

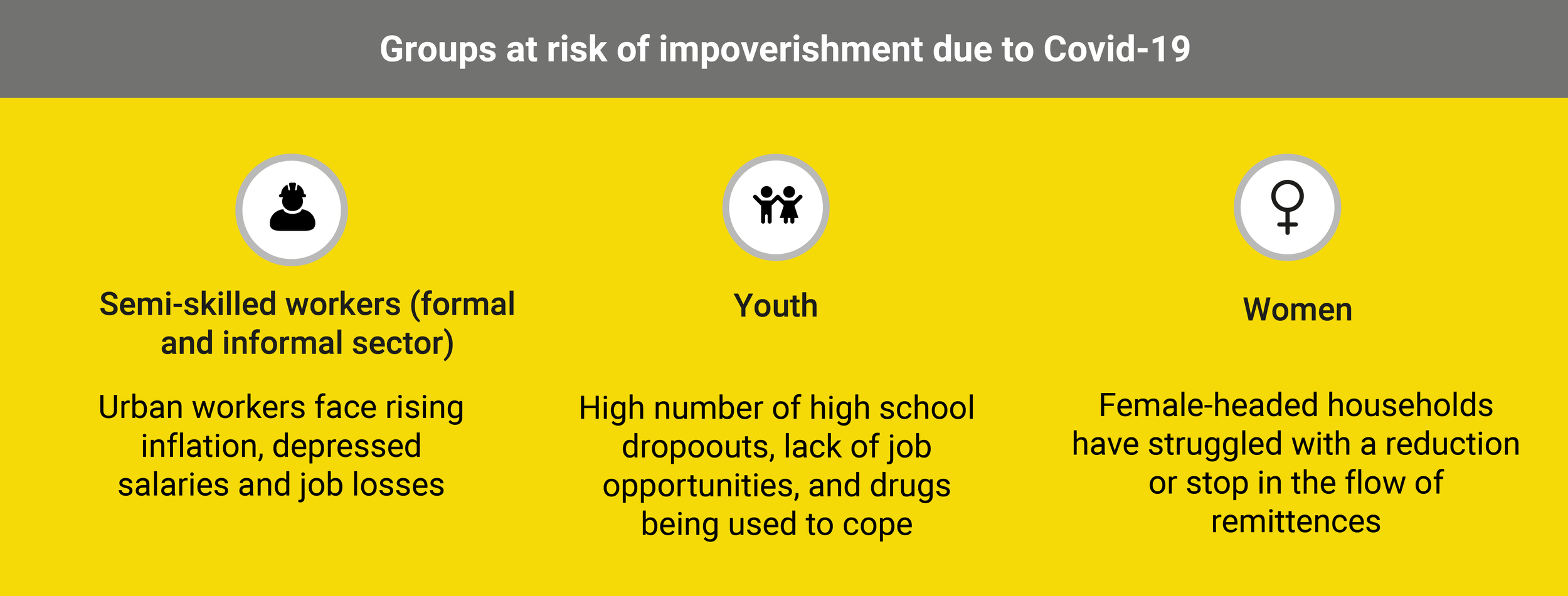

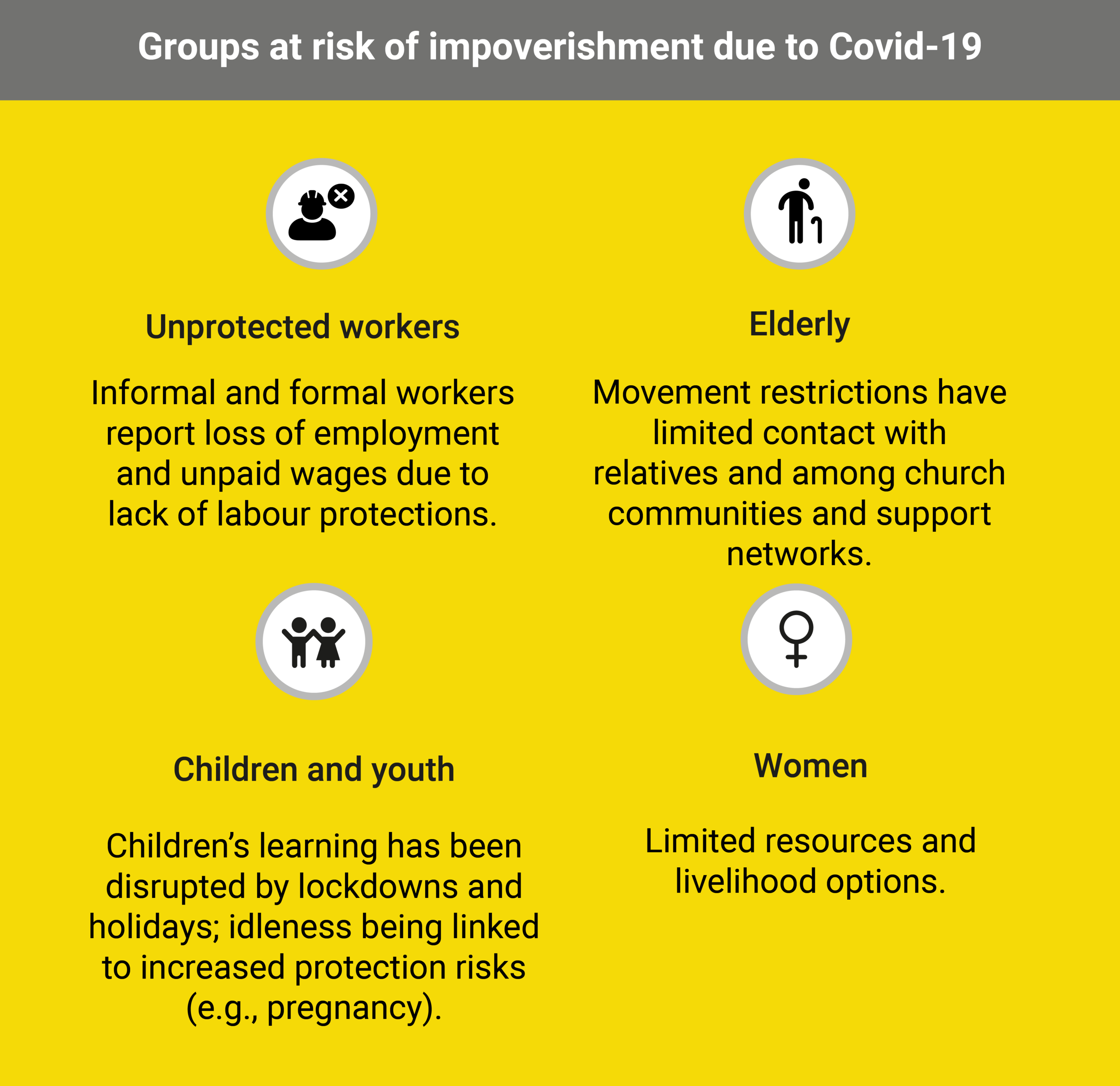

Groups at risk of impoverishment due to the COVID-19 pandemic

Recovery in well-being has not been experienced evenly, with some failing to see their well-being bounce back as lockdown restrictions relax. Many still face further impoverishment. Unemployment and underemployment are widespread. Hyperinflation was mentioned by almost every sentinel household, whatever their wealth status, as reducing their standard of living. It worsens the effect of the pandemic and bites deeply into household budgets. Widespread livestock diseases have also had a profoundly negative effect. Downward mobility from these shocks has been compounded by the impact of climate change, experienced through cyclones, more frequent droughts, and rain variability, with negative impacts on livelihoods, food security and resilience.

Semi-skilled workers (formal and informal sector)

Urban workers: increased risk, with rising inflation alongside depressed salaries and widespread job losses.

Borrowers: widespread indebtedness, with households borrowing to survive during the pandemic now falling into arrears. This is particularly acute in urban areas, where residents have accrued rental and utility debts.

Urban households: many have failed to recover from job losses triggered by COVID-19 lockdowns (including factory workers, informal traders, bus conductors, drivers, and hairdressers). Some have moved into adverse forms of coping, such as reduced food, distress migration and transactional sex.

Business owners: nearly one in five rural households reported a drop in business income as one of the effects of Covid-19 in 2021.

Women

Women headed households: the flow of remittances reduced or stopped at the start of the pandemic, particularly affecting de facto women-headed households. In Zimbabwe, two in every five households were female-headed. Remittances are increasing slowly but from a low base. Many international migrants lost their jobs and are struggling to find new ones, particularly as the rise in xenophobia in South Africa increases the challenges of the job search.

Female cross-borders traders: not yet returned to the former level of well-being, as borders have only recently re-opened and traders need to re-establish their trading links, which had largely broken down over the past two years.

Youth (15-35 years)

NEETs: 45% of young people (aged 15-24) were not in employment, education, or training (NEET) (ZIMSTAT (2020). 2019 Labour Force Child Labour Survey report. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT), Harare, Zimbabwe).

Secondary school children: High drop-out rates amongst secondary school children, with reduced interest in education and many opting to work and contribute to household welfare instead.

Children from poor households: Reduced household incomes mean that many parents are unable to pay fees and other school and college expenses. Some have fallen into arrears, putting their children’s school places in jeopardy.

Unemployed youth: Unemployment has increased, particularly amongst the youth, who are struggling to find work and build up an asset base. A young person’s first job is hugely important, potentially setting their path in life, and the longer they are unemployed, the harder it is to find high-quality employment.

Drug and alcohol users: Drug and alcohol use is increasing, as youth seek to cope.

Areas of concern for the poorest and potential impoverishment

Ranking of self-reported impacts

The biggest changes that people in Zimbabwe said the pandemic had made to their lives were:

Loss of educational opportunities for children

Reduced household income as a result of lockdown restrictions.

Lost education: Missed learning was cited by many people, including the poorest, as the worst consequence of the pandemic. Many children missed almost two years of schooling due to the lockdowns. Poor and rural children have been the worst affected by reduced learning outcomes, as access to online learning was limited, further entrenching inequalities.

“Only urban learners of better off classes could afford virtual learning, but the contrary is true with our rural folk.” Thambo, 86, woman, Tsholotsho, poor well-being group.

“How many parents even own smart gadgets or laptops. That approach was never practical for 99% of us.” Thulani, 37, woman, Tsholotsho, resilient well-being group

Unaffordable education: Nicole, a vegetable vendor in Bulawayo explains how COVID-19 affected her children’s education:

“The most important impact on my household has been the gap in learning that my children suffered because of not attending school. I feel that I have failed as a parent because I had no income at that time and so could not afford to pay for the children to do extra lessons. The charges were US$10 per child, per month, on average. This meant that for my three children to learn I would have had to pay US$30 a month, which I did not have. In addition, I could not afford the ICT gadgets that were a requirement for the children to do online learning.” Nicole, 40, woman, poor well-being group, Bulawayo.

Indebtedness: When schools re-opened in mid-February 2022, many parents did not have the savings to pay school fees. Others, with accumulated debts from previous years, were barred from sending their children back to school until the debts were cleared. Thenjiwe, a 55-year-old builder in Tsholotsho (poor well-being group), laments: “The children are back at school though we still have not paid school fees to date,” so, his children cannot attend. However, people place such value on education that some reported clearing arrears and paying the new term’s school fees so that their children could return to school even while the family was so severely food constrained that they were surviving on only one meal a day.

Reduction in income

Job losses and reduced remittances. Job losses were also triggered by border closures and reduced business revenues.

“Ever since the outbreak of the novel virus, a lot of our children have lost jobs in the diaspora, in particular in South Africa and Botswana.” Very poor well-being group, Tsholotsho.

Income Losses: The lockdown drastically reduced household incomes across study sites and across income and livelihood groups, reducing people’s quality of life. Many households are recovering, slowly, but are struggling to regain their former standard of living. ZIMVAC found that around half of all rural households experienced reduced sources of income and a loss of employment (52% in 2020, 48% in 2021). Reduced discretionary spending squeezes retail and service sector profits and this trend continues as hyperinflation compounds the impacts of COVID-19.

Limited freedom of movement to search for job opportunities, particularly in the context of lockdowns, impaired the ability of households to respond to income shocks.

“The pandemic dried up my income sources, namely remittances and petty trading. My children lost their jobs during the pandemic and limited movements made it difficult for my daughter to venture into any other income generating activities.” Destitute/extreme poor well-being group, Chitungwiza.

Increased business costs: Social distancing meant that markets closed. Brenda, an informal trader in Bindura (vulnerable but not poor well-being group) explained that market closures and travel restrictions ruined her business because rather than source goods herself, she had to pay for runners to go and order goods for her from Mutare and Harare and bribe the police to let them travel, despite the restrictions. This slashed her profits, but her business survived, and she is now rebuilding it to pre-COVID levels.

Retreat into subsistence: Some farm households have withdrawn from markets in the face of hyperinflation, retaining produce for self-provisioning.

Shocks and disasters overlapping with COVID-19

A number of other shocks and disasters overlaid the COVID-19 pandemic shocks (hyperinflation, indebtedness, distress migration, food insecurity, health and social shocks, livestock disease, as well as weather-related shocks) seriously affecting wellbeing and reducing household’s ability to cope.

Economic shocks

Hyperinflation was ranked as the most important shock, affecting all four study sites, both rural and urban, and by all wellbeing groups. At the beginning of 2022, ordinary people were alarmed by the skyrocketing prices of basic goods and services and the worsening exchange rate. These are driving up the cost of living and eroding households’ purchasing power. Many have lost the value of their savings. Salaries and pensions are nearly worthless. ZIMVAC found that the most prevalent shock in 2021 was cash shortage (experienced by 57% of households).

The local currency, known as RTGS or Zimbabwe dollars, is fast losing its value against other currencies. Retailers prefer to deal in United States Dollars ($) or South African Rand and “charge commodities a notch higher if they were being purchased with the RTGS”.

Brian in Bindura complained that business owners are still short-changing them by charging exorbitant prices using parallel market rates (currently Zimbabwe is using multiple currencies with official and parallel exchange rates), which are beyond the reach of an ordinary person in the rural areas. He gave an example of increases in the price of a bottle of cooking oil from $4 in November 2021 to $4.80 in March 2022 and $1 for a loaf of bread in November 2021 to $1.2 in March 2022. In RTGS values, cooking oil increased from about RTGS 450 in December 2021 to RTGS 1,000 in March 2022. (Poor well-being group, Bindura).

Hyperinflation drives up the cost of urban residential rents and utilities every month. Nicole of Bulawayo commented that her well-being was being affected by inflation and the dramatic increase in the cost of her water bill. (Poor well-being group, Bulawayo).

“Food and non-food groceries have skyrocketed. 500 Rand could buy way more before Covid-19 than it can now.” Thambo, poor well-being group, Tsholotsho.

Hyperinflation is driving up the cost of health care and school fees so that an increasing proportion of the population, including the previously non-poor, are unable to meet their basic needs.

Indebtedness increased during the pandemic amongst non-poor households (vulnerable but not poor, and in a few cases, resilient households) as well as amongst the poor (refer to Wellbeing Categories and Characteristics). Many urban households struggled to both buy food and pay rent and fell into rent and utility bill arrears.

Nkosana in Bulawayo was unable to pay his rent on time during the lockdown. This affected his relationship with his landlord, who became antagonistic and threatened to evict him. The situation has improved again, as he has gradually managed to resume regular rental payments. (Poor well-being group, Bulawayo).

Charity, an 81-year-old widow in Chitungwiza, has been in arrears for more than 10 months now. She is afraid that her household will have to return to living in the rural areas if the council evict her because of rent arrears. (Destitute/extreme poor well-being group, Chitungwiza)

Distress migration: Distress migration is a drastic coping strategy. An estimated three million Zimbabweans lived abroad in 2015, and that number is almost certainly higher today. It usually involves one or more household members seeking work in another country and sending remittances to support the people they have left behind. This coping and risk spreading strategy are common in Zimbabwe, especially in regions of low agricultural potential, such as Matabeleland.

The research found that the dire economic situation has driven many to migrate. Nkosana, a 42-year-old man in Bulawayo (poor wellbeing category) says his wife has been pushed by falling household income to leave to look for work in South Africa. She has not been able to remit any money to help with household expenses yet. Nkosana complains that this is effectively a breakdown of the family unit, and it has greatly affected the children, as he cannot play the role of mother as well and his older children have had to take on the responsibility of looking after their younger siblings. (Poor well-being group, Bulawayo).

In Bindura, Beauty a 65-year-old widow (poor wellbeing category) indicated that both of her children had migrated. Her son is back at work in Mozambique, while her daughter is looking for a job in Zambia. Her son regularly sends his mother kapenta (tiny, dried fish, Tanganyika sardine), which she sells, making the income that she lives on (poor well-being group, Bindura).

Charity, an 81-year-old widow, lives with her daughter and grandchildren in Chitungwiza. Her son lost his job in South Africa during the pandemic and is struggling to earn money. This means the money he sends back is irregular, having a negative impact on their household. For example, her grandchildren had to delay returning to school for two weeks as their parents did not have enough money to pay school fees.

Christine, who lives in Chitungwiza, has a grandson living in South Africa. He used to send regular remittances but now he sometimes fails to send them anything at all. She understands that he is under pressure. The company he worked for downsized, and he is married now and has to use his disposable income to provide for his new family in South Africa. Christine lives with her six other orphaned grandchildren, and is now destitute, in the extremely poor wellbeing category. She has limited the number of meals they have a day and reduced the quality of food they eat. They cannot afford to eat meat. Christine is worried that the children may suffer from malnutrition.

Rural-urban links under pressure: Rural-urban linkages are a strong feature of Zimbabwean life, with many urban residents having a rural base. There are also high levels of internal migration, with an extended family spread over a wide geographic area, working in different livelihoods. This spreads risk and enables diversified sources of income across the network. There are two-way support systems between rural and urban areas with rural residents providing food, in particular maize, beans, groundnuts and pumpkins to urban family members, especially when they produce a bumper crop. When the rural side of the family is struggling, from drought or another shock, the urban-based members send help. During the pandemic, the shock was so widespread that it overwhelmed these traditional safety nets, and family members could no longer provide the traditional support to other members. This resulted in desperation, where some households were pushed to adopt adverse coping such as distress migration out of the country, borrowing, begging and transactional sex.

Nathan (31) a self-employed mobile phone repairer lives alone in Bulawayo (vulnerable but not poor well-being group). His income has fallen, with negative consequences for his rural extended family as he can no longer afford to send them groceries or money. This has affected his relationship with them. Nathan thinks that his parents feel that “the city life has swallowed him, and he has abandoned them”.

Nonthandazo and her husband are based in Bulawayo (vulnerable but not poor well-being group). Although they are not poor, hardships from the Covid-19 lockdowns pushed Nonthandazo to migrate to their rural home for a short time, to reduce their spending on food.

“The challenge of not being able to work affected both me and my husband. On my part, I had to move back to our rural home in order to engage in farming. At first, it was difficult for me to adjust to rural life because I was now used to city life. I gradually adjusted although it was difficult to live far away from my children and home.”

Some whole households undertook urban-rural migration to reduce household spending, particularly on food and rent. Rural extended family networks facilitate such moves by, for example, providing a plot of land so that the migrants could cultivate and become food sufficient. They often also helped build houses (mud and thatch huts) and shared agricultural implements.

Experience shows that retreating to the rural area is a key coping strategy for urban families in hard economic situations, not only for the poor and very poor but also for the non-poor, such as Nonthandazo.

Social

Xenophobia in migrant destinations: Migrants to South Africa are facing a rise in xenophobia alongside depressed job markets. Many who lost their jobs during the pandemic have not been reinstated, as the COVID-related recession has reduced job opportunities and new regulations for foreign workers have been introduced. These factors combine with xenophobia to exclude Zimbabweans from job opportunities in South Africa, and employers increasingly prefer to hire fellow South Africans. There are pressure groups in South Africa such as Operation Dudula, a group of anti-immigration vigilantes that reinforce discrimination against foreigners. A Zimbabwean man, Elvis Nyathi a gardener, originally from Matobo District Matabeleland South, was horrifically murdered in April 2022, by anti-migration protesters in Diepsloot township, north of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Teresa, an 81-year-old widow in Tsholotsho (very poor wellbeing category) explains that her family’s wellbeing has since worsened because her children cannot send her enough groceries or remittances from South Africa. They lost their jobs in the pandemic and are still unemployed. They will probably move back to Zimbabwe soon, as their permits allowing them to stay in South Africa legally will expire soon and are unlikely to be renewed.

Gendered impacts: Women now face an increased burden of unpaid household work. Many young girls dropped out of school, and others were compelled into early marriage. Child marriage was already high in Zimbabwe, with about 1 in 3 (34%) of girls under 18 years being married.

“Women and girls have suffered more than men and boys especially on unpaid household duties. There was a lot of burden on girls and women because they have to do household labour like laundry and cleaning. Educationally, due to low income, boys were allowed to go to school while girls were forced to stay at home and others were forced into marriage due to these challenges.” Brian, 22, well-being group, poor.

“The number of children that returned to school after 8 February 2022 is less than 75%. I estimate that three out of ten girls, aged between 14 to 16 years, did not return to school due to teenage pregnancy and domestic work. I also estimate that two out of ten boys, aged between 15 to 18 years, did not return to school due to marriage and drug abuse.” Brian, 22, well-being group, poor.

“COVID-19 has impacted more on women and girls than on men and boys. Women were now forced to take on the hard work normally done by men, especially those women-headed families and also girls … dropped out of school in order to find jobs or got married.” Bianca, wealthy well-being group.

“When poverty strikes a household, everyone feels the impact no matter age or gender.” Benjamin, resilient well-being group.

Health

Physiological stresses include fear of contracting COVID-19 and the inability to mourn the dead.

“We lost neighbours and friends during the peak of COVID-19, and it was so painful because we could not even gather for the burial to bid them farewell’ (Teresa, 81, widow, very poor wellbeing category, Tsholotsho).

Sexually transmitted diseases: The drop in income affected some households’ health. Noah, a 24-year-old orphan, is an informal worker who is looking after his six younger siblings in Bulawayo. His household, which is in the very poor wellbeing category, is an example of the negative social consequences that resulted from the shocks brought about by COVID-19.

“The most important impact on my household has been the dramatic reduction in my income that has caused all the other problems I now face. Together with my siblings, we are living from hand to mouth. We must cut down on meals and the quality of food we now eat. To add on to this, my sisters’ health is now compromised as they are now at risk of contracting sexually transmitted infections because they have resorted to having boyfriends who can provide for them in terms of personal ware like toiletries, mobile phone airtime and sanitary wear.” Very poor well-being group, Bulawayo.

Drug abuse: The use of alcohol and illegal drugs to cope with social stresses and their lack of opportunities has increased amongst young people. A young self-employed barber in Bindura started taking drugs when he began to struggle after his business collapsed due to the lockdown. He became addicted to drugs including mutoriro or crystal meth (methamphetamine), Bronclear (a brand of cough medicine containing codeine and alcohol) and marijuana, in order to cope with stress. He explained that he is still addicted to drugs and:

“It is my hope that my return to work will keep me busy and occupied so that I will manage my addiction to drugs.” Bindura, poor wellbeing category.

Chipo, a young woman, in the very poor wellbeing group, lives in Chitungwiza with her younger brother who is a drug addict. She said:

“Since we spoke in November (2021, during the first round of PMI interviews) my brother has been hospitalised for his crystal meth addiction. I thought he was recovering but he did not take much time before he relapsed. I think it was because he came back into the same stressful environment. Very poor well-being group, Chitungwiza.

Food security

Limited food quality amongst the poor: Food security improved amongst most households between November 2021 and early 2022, although some are still struggling. The majority of poor households increased consumption from one to two meals a day and are eating better quality food again. Amongst them are those who have started receiving remittances again or who have found work. For example, Beauty’s son re-started his job in Mozambique and has started sending her remittances again (poor well-being group, Bindura). However, many still do not have enough to eat and food quality is still poor, with many unable to afford protein, relying instead on a diet of maize and green vegetables. Several respondents commented: “We eat for survival, not for enjoyment”.

Some households depending on income from retail or service micro-enterprises are seeing continued declines in well-being, as consumer spending is squeezed by the impacts of unemployment, enterprise failure and hyperinflation. Some others anticipate worsening food security in the coming months due to the impact of hyperinflation, the worsening exchange rate and poor rains.

“The food situation is still worsening. This is mainly due to the poor rains and the ever-increasing prices of maize meal, flour, and cooking oil.” Themjiwe, 55, male, poor well-being group, Tsholotsho.

Even richer families have seen luxuries disappear from their diets, such as yoghurt and ice cream, and bread is sometimes substituted with maqebelengwana (a bread made from mealie meal) or isimodo (a type of thick bread made using flour and water). Some of the ‘less desired foods’ are more nutritious than their regular diet and provide health benefits, such as soya chunks, beans, wild vegetables such as okra, Bidens pilosa (blackjack) and Amaranthus hybridus (pigweed), as well as edible insects.

Extremely poor households are still food insecure. Some have experienced weight loss and poor health due to poor nutrition, especially among older people. In Bulawayo, Nkosana, a casual labourer, describes his family as an “underfed household, where there is not enough food to eat, and …. sometimes we are in the situation whereby there is no food at all”.

Casual labourers still struggle to find paid work as households who would normally employ them are still reducing their discretionary expenditure. “The local community still cannot afford to hire us as casual labour.” (Tabitha, 54, female, very poor well-being group, Tsholotsho).

Improvements amongst the non-poor: non-poor households were found to have returned to eating three meals a day, and meat once a week.

“I am now buying meat, bread, and butter as I wish so that I can get back my weight lost during the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic. So, I buy two loaves of bread and two kg of beef enough for me and my domestic worker. It is only that I am left with very few teeth in my mouth, I wish I had all my teeth to chew all the meat!” Woman, resilient well-being group, Bindura.

Food insecurity depends on self-provisioning: for many in Zimbabwe, food security depends on self-provisioning. This has become even more the case in the face of hyperinflation and a worsening exchange rate. Even urban households attempt self-reliance and some Chitungwiza residents (an urban area near Harare) farm at their ‘rural homes’ and grow enough to meet their needs in good rainfall years. For example, Christine, an 83-year-old widow (extremely poor wellbeing category) used to farm at her rural home in Wedza (Mashonaland East Province) as well as engage in urban agriculture. But she is no longer able to farm as she is recovering from a stroke, so did not grow any crops at all last season. As a result, her family does not have enough food stored for even a month, and without an income to enable them to buy off the market their future food security is precarious.

Weather-related shocks

COVID-related shocks overlay numerous other shocks and weather-related shocks are particularly significant. ZIMVAC found that waterlogging (related to flooding) was experienced by 45% of households in 2021. This was the second most prevalent shock in 2021 after cash shortage, followed by drought (26%) and livestock deaths (21%).

Cyclone Ana : Bindura was negatively affected by Cyclone Ana, which hit north-eastern Zimbabwe in January 2022, causing heavy rains and flooding, and affecting at least 3,000 people. The farmers in Bindura estimated that cyclone Ana destroyed 75% of the crops. Houses, schools, and roads were also destroyed.

“Cyclone Ana was one of the shocks that drove people in this area into poverty.” Very poor well-being group, Bindura.

“The cyclone took the roof of my house off and destroyed some of my furniture, like sofas and beds. It also killed all the 100 broiler chicks for my poultry projects and destroyed other people’s crops and infrastructure.” Brenda, resilient wellbeing category, Bindura.

“Cyclone Anna affected my area with massive destruction of infrastructure, for example the dirt roads, school roofs like Manhenga primary school and other houses were destroyed. Furniture was also destroyed. Fortunately, no lives were lost but all the crops were destroyed and swept away.” Bruce, vulnerable but not poor wellbeing category, Bindura.

The farmers reported that the rains during the cyclone were followed by a protracted dry spell that destroyed crops all over again. They predicted that this year would be a drought year.

“After Cyclone Anna, there was a serious dry spell that followed……the crops that survived cyclone Anna did not (all) survive the dry spell, which lasted for about three weeks from mid-February to 1 March 2022. Soon after that dry spell, there was a hailstorm that destroyed tobacco and farmers had to write off their crops. So, this year there is drought. Again, too many people who did not plant small grains are likely to be food insecure owing to a dry spell which lasted for a month.” Brian, poor well-being group, Bindura.

Droughts seriously affected the wellbeing of farm households in Tsholotsho, reducing food security. The rains stopped abruptly before the crops had matured. Some recorded low yields, while others experienced complete harvest failure. The drought also affected the mopane worms (a popular wild food), which did not thrive this year, resulting in a low harvest. The low yields left households food insecure.

“I have suffered a great loss this year due to the heavy rain followed by a dry spell. This drought affected my crops, especially maize, and they were written off. Only a small piece of sorghum has survived.” (Beauty, poor well-being group, Bindura).

“Even amacimbi (mopane worm) never did too well this time around. The ancestors are probably not very happy with the things that your young ones are doing in this world, so they have taken the rains away early.” (Very poor well-being group, Tsholotsho)

“Crop production for the 2021/22 season is disappointingly low because of the insufficient rains, which went away just before crop maturity.” (Poor well-being group, Tsholotsho).

Livestock disease: Livestock losses from January Disease (theileriosis) (2018-22) have had a devastating effect on farmers, driving asset losses and, in some areas, leaving the majority of households without draught power, limiting cultivation and agricultural production. This led to smaller areas being ploughed, and lower production, contributing to food insecurity. The loss of livestock also impaired households’ ability to cope, as it removed the option of selling cattle to meet contingencies.

Teresa, a farmer in Tsholotsho (very poor well-being group) emphasised that January Disease was the most prominent disease that affected the cattle in the community.

The Department of Veterinary Services provided farmers in Bindura with medication and access to dips to control ticks. They recommend vaccination and dipping cattle twice a week and this regime has stabilised the situation, leaving farmers optimistic that this outbreak of January Disease is over. Some livestock were still dying of January disease in January 2022, but the incidence has dramatically reduced.

Coping strategies

In early 2022, people were still employing a diverse range of coping strategies. They were carefully prioritising expenditure and forgoing luxuries. Reducing the number, size and quality of meals was the most widely adopted coping strategy, and was reported by all wellbeing groups, except for the resilient and wealthy (categories 5 and 6). Migration and remittances, together with livelihood diversification were also frequently cited coping strategies. Others included: urban agriculture; sub-letting urban homes; borrowing; reverse migration from urban to rural areas; illegally circumventing lockdown rules and transactional sex.

“We adopted coping strategies like reducing meals and getting support from parents and relatives who are also struggling to make the ends meet. For school fees, I was enrolled into the Basic Education Assistance Module (BEAM) funding from the government, and I sometimes get free meals at school when schools are open. I also reduced meals and resorting to poor quality food obtained after engaging in casual labour. These strategies have worked but it impacted on the health and wellbeing of my family. My parents had to work tirelessly to bring food on the table. The food we were eating was not good since we would eat anything that came our way. We are very fortunate now that the situation has changed due to the lockdown relaxation, and my parents are back at their informal business and are getting a little that can help us to survive and go to school.” (Branson, 18, poor well-being group, Bindura).

“We relied on leasing out some hectares of land, as well as the pension from my father but it is not enough to cater for the family. I sometimes would have to use illegal means to order my goods for resale. There are illegal transport operators who were helping me to smuggle shoes from Mozambique although it was very expensive. To a greater extent, these coping strategies have helped much even though it was not a walk in the park.” (Billy, 28, informal trader and farmer, vulnerable but not poor well-being group, Bindura).

Once the lockdown was relaxed in January 2022, Billy’s situation improved. His income grew and he and his family are getting back to normal again.

Some households found that their preferred form of coping was insufficient. They were forced to adopt adverse coping mechanisms, which resulted in an increase in social harm, created long term damage and impaired resilience and the ability to move out of poverty. We found adverse coping to be widespread (engagement in, for example, transactional sex and artisanal mining) and hyperinflation, the reduced harvest likely in 2022 and any subsequent shocks will have negative consequences for a population that has largely already exhausted its resilience and ability to cope safely.

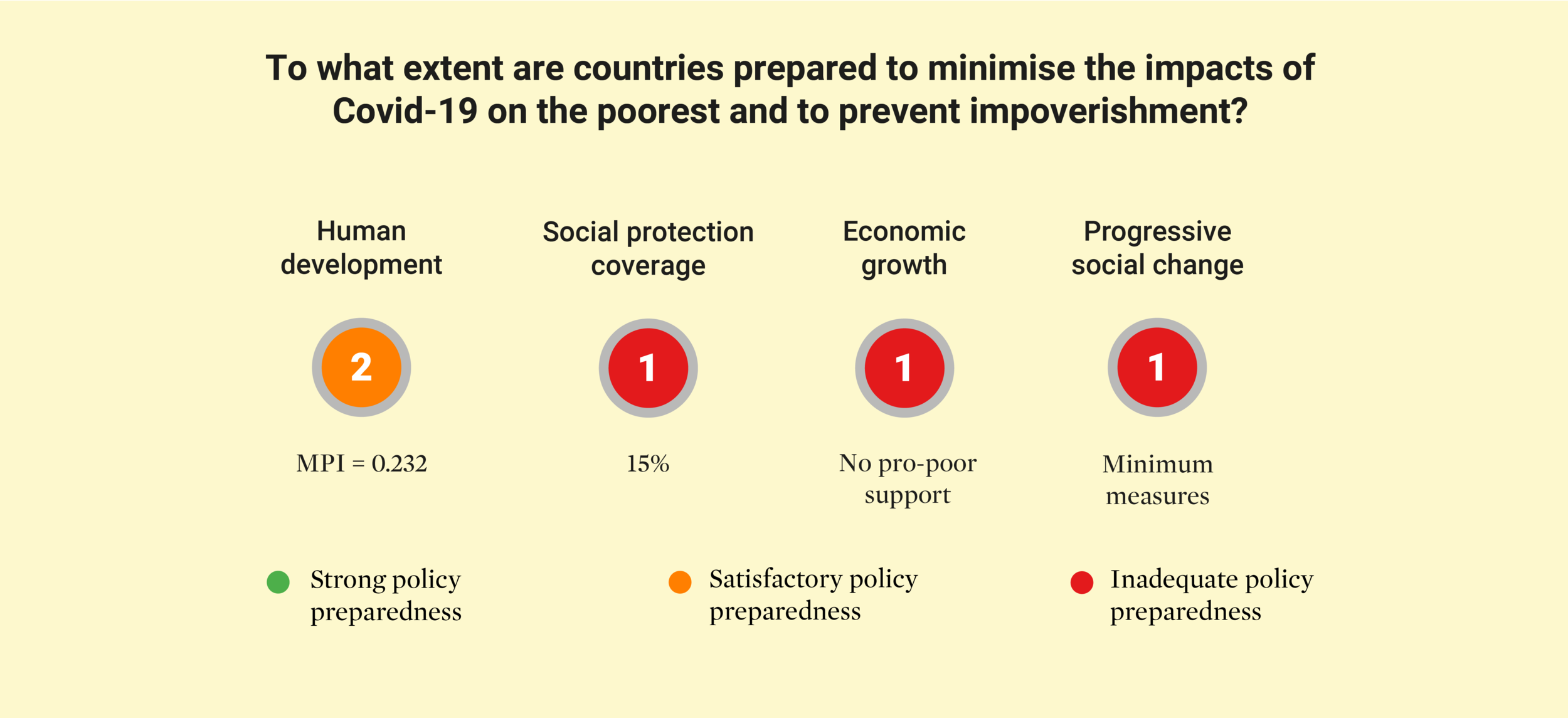

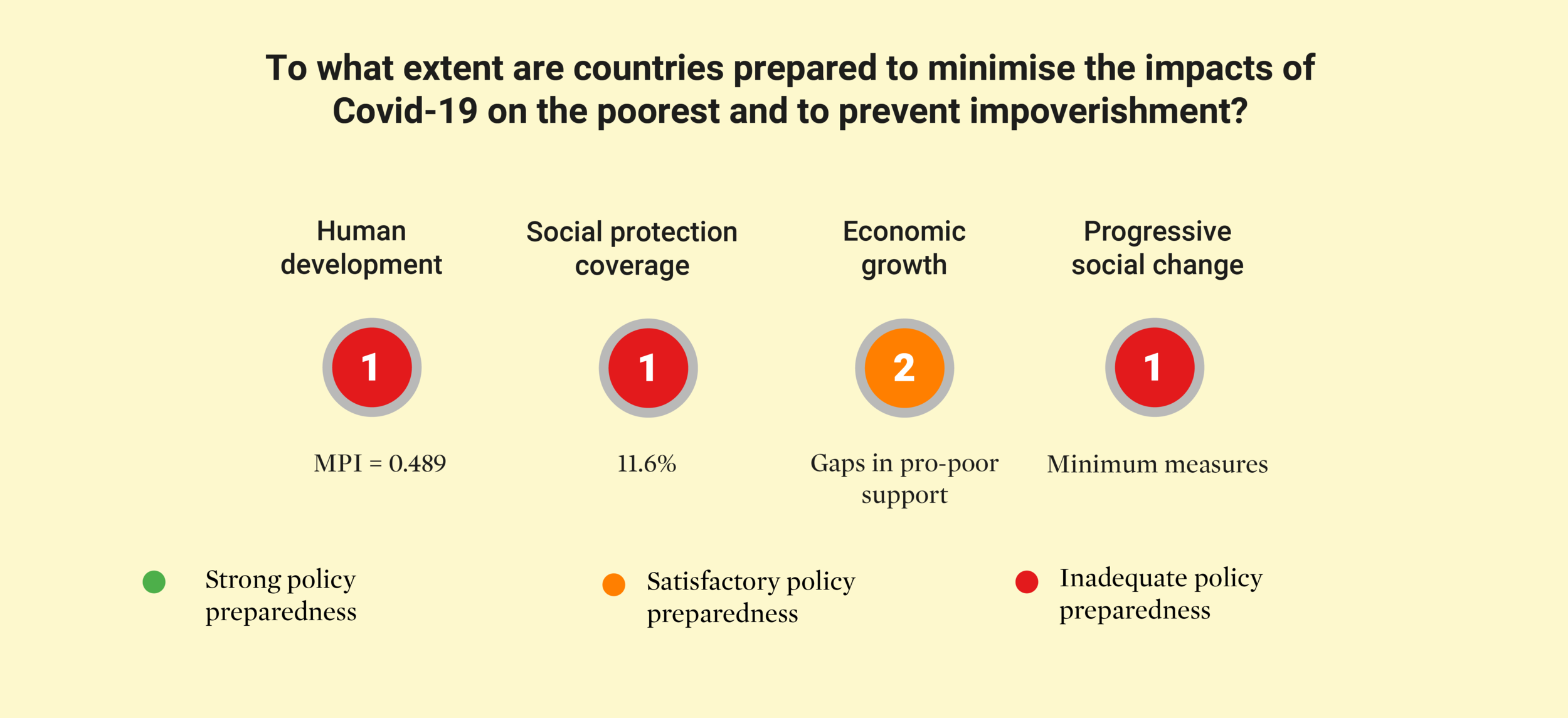

Programmes to mitigate impoverishment

A number of social protection and food security programmes are in place in Zimbabwe, provided by the Government, international development partners and NGOs, including:

Food assistance

Cash transfers

Agricultural inputs

However, the social protection system failed to systematically protect well-being. Inadequate transfers and low coverage meant that the majority did not receive cash transfers or food aid during the height of the lockdown, even if they were extremely poor or destitute. So, by November 2021, only 12% of households nationally had received food assistance in the form of grain distribution. The survey found that 19% of the food assistance was provided to households in rural areas compared to 1.2% in urban areas. Only 4% of households received Covid-19 cash transfers, with fewer rural than urban households in receipt and only 3% of households received any other form of cash transfer.

Our data confirms this extremely low-level support, with respondents in March 2022 stating that they received very little support from either Government or non-governmental organisations. Negligible support was reported by PMI respondents in Bulawayo, Chitungwiza and Tsholotsho, but some participants in Bindura received Government social protection assistance, most of them older people. In contrast, all households in the two rural PMI study sites received inputs for planting one acre from the Government’s Pfumvudza/Intwasa conservation farming programme for smallholder farmers, plus advice from the local AGRETEX officers about zero-tillage agriculture. (The Input Package for a Pfumvudza/Intwasa Plot was consistent across the rural research sites, Bindura and Tsholotsho and distributed through the Presidential Inputs Programme. The package consisted of 2kgs seed (maize or sorghum), 12kg lime, 16kg Compound D, 16kg Ammonium Nitrate, and insecticide for pests.)

Social protection assistance

People in Bindura received a wider range of social protection assistance than at the other study sites, though it was targeted mainly at older people, and disbursement of the support package was reported to be ‘inconsistent’, with frequent delays.

“Yes, currently my old parents are receiving …. assistance from the government through the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare in the form of food stuffs: 20kg maize, 2 litres cooking oil, 2kg sugar, and a sum of $5 per month.” (Very poor wellbeing category, Bindura).

Older people also receive free medication from government hospitals and are exempted from user fees.

Children from poor very families may qualify for the government’s BEAM programme (Basic Education Assistance Module) which gives recipients school fee exemptions and free school meals. Branson is now 18. When he first began secondary school, he was enrolled in because the School Development Committee identified his parents as not being formally employed and struggling to pay school fees.

“During this time when schools are open, we get free porridge in the morning at our school and sadza and beans on Monday, Wednesday and Fridays and it is available to every learner.” (Poor well-being group, Bindura).

Assistance from relatives and churches

In Tsholotsho, Chitungwiza and Bulawayo poor households did not report receiving any formal transfers, with the only support coming from remittances and some church support for older people. For example, an elderly widow in Chitungwiza receives no government transfers and instead relies on support from her Church, despite supporting six orphaned grandchildren.

Pensions and medical insurance

Pensions coverage is very low in Zimbabwe, with only 2% of the population receiving a monthly pension or social protection transfers in 2019. While several older respondents in Bulawayo and Chitungwiza reported receiving occupational pensions, their value has been eroded by inflation, leaving the recipients struggling. Medical insurance coverage is also low, covering only 7% of the population, mostly employed by private enterprises in the non-financial sector or in central government.

Methodology

CPAN country bulletins are compiled using a combination of original qualitative data collected from a small number of affected people in each country, interviews with local leaders and community development actors, and secondary data from a range of available published sources. Interviews were conducted with 40 households for this bulletin, across four study sites (Bindura Rural District in Mashonaland Central Province; Tsholotsho District in Matabeleland North Province; Nketa suburb of Bulawayo; and Chitungwiza, Harare Metropolitan Province), in March 2022, in addition to local key informant interviews.

More details on the sampling and methodology for this bulletin can be found here.

This bulletin was created in collaboration with the University of Zimbabwe and made possible with support from Covid Collective.

Supported by the UK Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), the Covid Collective is based at the Institute of Development Studies (IDS). The Collective brings together the expertise of, UK and Southern-based research partner organisations and offers a rapid social science research response to inform decision-making on some of the most pressing Covid-19 related development challenges.